Back in May, our book club read Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, and we all loved it. Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet tells the story of the evacuation and internment camps of the Japanese-Americans during WWII. What I love about this one is that it’s told through the eyes of a Chinese-American boy who befriends a Japanese-American girl. The way he sees things is very different from his father’s perspective, which adds another interesting element to the story. If you decide to read this book, be ready to cry.

Back in May, our book club read Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, and we all loved it. Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet tells the story of the evacuation and internment camps of the Japanese-Americans during WWII. What I love about this one is that it’s told through the eyes of a Chinese-American boy who befriends a Japanese-American girl. The way he sees things is very different from his father’s perspective, which adds another interesting element to the story. If you decide to read this book, be ready to cry.

“I was born here. I don’t even speak Japanese. Still, all these people, everywhere I go… they hate me.”

As he left the hotel, Henry looked west to where the sun was setting, burnt sienna flooding the horizon. It reminded him that time was short, but that beautiful endings could still be found at the end of cold, dreary days.

He’d do what he always did, find the sweet among the bitter.

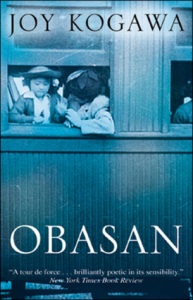

Two years ago, I read Joy Kogawa’s excellent book, Obasan. (My review.) Based on Kogawa’s own experience, Obasan tells the story of a young Japanese-Canadian girl during the war as she and her family get separated and sent to internment camps in Alberta, never to return home.

Two years ago, I read Joy Kogawa’s excellent book, Obasan. (My review.) Based on Kogawa’s own experience, Obasan tells the story of a young Japanese-Canadian girl during the war as she and her family get separated and sent to internment camps in Alberta, never to return home.

If we were knit into a blanket once, it’s become badly moth-eaten with time. We are now no more than a few tangled skeins – the remains of what might once have been a fisherman’s net. The memories that are left seem barely real. Grey shapes in the water. Fish swimming through the gaps in the net. Passing shadows.

The Translation of Love takes these stories of North American internment camps a step further – it takes us to Japan after the war has ended.

The Translation of Love takes these stories of North American internment camps a step further – it takes us to Japan after the war has ended.

12-year-old Aya and her father have returned to Japan from Canada after the war. The Japanese-Canadians were given the choice of dispersing east of the Rockies or repatriating to Japan. Aya’s father did not want to stay in a country that betrayed him the way it did, so he chose repatriation. But coming back to Japan is not easy; the country is devastated and starving, and Aya’s father struggles to find work so that Aya can continue going to school. Aya doesn’t fit in; she looks Japanese, but she is Canadian. She talks ‘funny’, has a hard time understanding everything that is said to her, and she doesn’t know how to act. She is miserable at school and does her best to make herself invisible.

The Translation of Love does not only tell Aya’s story; it alternates between the stories of several characters, all of which are connected in some way, but who all have very different lives and experiences in this new American-occupied post-war Japan.

There’s Fumi, the girl who eventually befriends Aya. Her sister has gone to work in the Ginza district and she hasn’t been home in a long time. Fumi is worried about her and wants to find her. She has heard that General Douglas MacArthur is here to help Japanese citizens, so she and Aya write a letter to him asking for his help to find her sister.

[First paragraph] Ever since her sister had gone away, Fumi looked forward to the democracy lunches with a special, ravenous hunger. The American soldiers came to her school once a week with deliveries, and though she never knew what they would bring, it didn’t matter. She wanted it all, whatever it was. Sometimes it was powdered milk and soft white bread as fluffy as cake. Sometimes it was delicious oily meat called Spam. Occasionally it was peanut butter, a sticky brown paste whose unusual flavor – somehow sweet and salty at the same time – was surprisingly addictive. The lunch supplements supplied by the Occupation forces reminded her of the kind of presents her older sister, Sumiko, used to bring in the days when she still came home. Fumi’s hunger was insatiable, and although she couldn’t have put it in so many words, some part of her sensed that her craving was inseparable from her longing for her sister’s return.

Fumi is not the only one writing letters to General MacArthur; hundreds of letters pour in everyday, waiting to be translated by employees of the occupation like Matsumoto (Matt). Matt is Japanese-American, and had never set foot in Japan until after the war was over. His family had been living in an internment camp, his brother one of the first to enlist in the war to prove their loyalty to the United States. Matt’s story gives us an idea of the divide between the Americans and the Japanese, as well as the general feeling of the Japanese people about the results of the war and the American occupation, through their letters.

There are also the Japanese translators who work in the alleys, translating or writing letters mostly for Japanese women who are involved with American soldiers.

… he came to see that the words were not just letters or symbols on the page. Each word was bursting with emotion. There were the emotions felt by the writer and by the reader, but also by him, the translator caught in the middle, reading secrets between lovers or dark truths shared.

Kondo is one of these men, trying to supplement his meager earnings as a school teacher. Through him we learn more about some of the changes taking place in the country and the education system; the push for Democracy.

Whatever was going to happen would happen – a new social studies curriculum, different classroom arrangements, American food for the school lunches. He had to admit that the students seemed to display no resistance at all. Maybe the Americans were right, and even if they weren’t, it didn’t matter because no one here could stop what was happening. Change was moving fast, like a giant tsunami, and Kondo did what everyone else around him did. He ran as fast as he could to keep from being crushed by the wave.

Through Sumiko (Fumi’s sister), we learn what it is to work in the dance halls, where the girls and women are expected to dance with the American soldiers, or more. They are drawn to the money and available food, hoping to provide for themselves or their families, but the jobs are not always what they imagined or hoped for.

Things happened fast on the dance floor or in the dark alleys. You had to develop a sense for danger, had to smell it coming before anything happened, before it exploded into something ugly, before it turned violent and hard. The safest way to react was not to react. To give in, to be passive. To fall limp, to make yourself small, to curl into yourself and not be a threat.

Underlying all these stories is the suffering the Japanese people have endured during the war and continue to contend with in the years following the war. But they also have a sense of hope that things will improve, and that Japan will once more be a great country. Their sense of hope and value of hard work is well illustrated by the Daruma doll that Fumi buys for Aya. It is a papier-maché of a monk’s head without any eyes. You think of something you want, then paint in one of his eyes. After you get what you want, you paint in his other eye. But you have to work for your wish; “He makes you work at making your wish come true”.

Maybe life came down to this. In the end there was only the task of moving forward, one step after another, making your way through the dust and dirt of living. You lived your own share of life, and if you could, perhaps you lived someone else’s share, too.

The Translation of Love is a wonderful addition to other works about the plight of the Japanese-Americans/Canadians during the war. What are others that you can recommend?

In an interview with Shelagh Rogers, Lynne Kutsukake explains the inspiration behind her novel.

In an interview with Shelagh Rogers, Lynne Kutsukake explains the inspiration behind her novel.

Read about Lynne Kutsukake’s own collection of daruma dolls.

In an interview with Paste, Kutsukake talks about her own connection to the internment camps and repatriation to Japan after the war.

“I wanted to write about the occupation period from the perspective of the people who we don’t often think about—from the perspective of Japanese-Canadians and Japanese-Americans, who, for different reasons, found themselves in Japan in this particular time. A time that was extremely turbulent and full of great change, but also a time that was full of immense potential and hope, because no one quite knew which way it was going to take off and how it was going to move. I think most people were just glad the war was over and to have survived. I was trying to get at that hope that people have. You just pick up and try to move forward.”

*Thanks to Random House Canada for providing me with a copy of this book. All the quotations included in this review are from an uncorrected proof.

Great reviews – I loved Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, have Obasan in my pile and am hoping to see Kutuskake at an author event in the fall.

Oh, a great excuse to read her book – it’s very good!!

How do you end up with the uncorrected proofs to read?

Random House Canada sent me this one!

just out of the blue?

Great review. Obasan is a Canadian classic I’ve read more than once it is so great. I’m looking forward to reading the others. You make them sound great, Naomi!

They are all so good! And complement each other very well. I hope you get a chance to read them!

Excellent review, Naomi. Such a fascinating area of history to explore. Obviously we had our own internment camps in the UK but I can’t think of an example of British fiction which explores that theme, or the idea of repatriation through choice. Gaping hole for someone to fill!

You’re right! I can’t think of an example, either. There were too many other things going on over there at the time, maybe?

It could be that although by now I would have thought someone might have picked up on it. The occupation of the Channel Islands hasn’t been much written about either in fiction.

So many good ideas!

For a slightly different angle, Cory Taylor’s book My Beautiful Enemy explores a relationship between a Japanese prisoner and an Australian soldier in an Australian internment camp.

Oh, thanks for the suggestion!

Also, I hadn’t thought about the fact that the same thing was happening in Australia!

Two others I’ve read on the topic are The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka and China Dolls by Lisa See. I think this one would be worth reading too — thanks for the review!

I have The Buddha in the Attic on my list – thanks for the reminder – I hear it’s good!

Wonderful review! 😃 Japanese internment is something I need to read more about, so horrible, and I also didn’t know anything about how this was handled in Canada!

For some reason I find it all fascinating. And, I haven’t read a book about it yet that has disappointed me.

Unfortunately, Canada has its many dirty secrets just like everywhere else. It was really a lot worse than anything we learned about in school.

I still have to read Obasan, but I can second Rebecca’s recommendation of China Dolls. And if you are interested in nonfiction, then The Train to Crystal City comes to mind. This one’s been on my radar since I first read about it on Kirkus Reviews. I’m glad you liked it just as much as that reviewer; now I know I have to read it. 🙂

I really loved it, and I think you will too!

I think I saw China Dolls last time I was at the thrift store, but I didn’t know what it was about so I left it!! Maybe it’s still there…

I’ve been meaning to read The Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet for a loooooong time. Thanks for the reminder. I had forgotten all about Obasan! I think it was assigned reading in university and I actually really liked it (early CanLit days 😉 ).

This book sounds intense! I really want to read it though! Excellent review, as always.

And yes – China Dolls was really good! My favourite of Lisa See’s!

Ok, next time I see China Dolls at a book sale, it’s mine! (I keep seeing it around, but didn’t know anything about it.)

I also had been meaning to read Hotel on the Corner for ages, so I was really happy when we chose it for book club. It’s so, so good!

When the Emperor was Divine by Julie Otsuka is another great book about Japanese-American internment. My TBR is growing and it feels good 🙂

That sounds like another good one – thanks for the recommendation!

It’s so good to see someone feeling happy about their growing TBR. 🙂

Yes our book group has read & liked The Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet too. It reminded me a bit of Snow Falling on Cedars from 1995, which is also a great read. I like that Lynne Kutsukake has a new take on internment life from Japan — that is a side I haven’t read before and will seek out her book — thanks. I hope she will come to the book festival here in the fall.

Oh, Snow Falling On Cedars was another good one! I read it long ago, so I don’t remember the details – a perfect candidate for a re-read!

This sounds really good- I see my library has it and I’m putting on the TBR.

Yay!

This was a book in the Keep Turning Pages Goodreads group before I became active in it. It definitely sounds like a good one! Love how you connected with the other two books. Have yet to read Hotel…too little time!

Good to hear people are reading it! All three are so good. Yes, always too little time… 🙂

No No Boy by John Okada. It’s set in Seattle in 1946. The narrator and his brother are first generation Americans, parents from Japan. The narrator refused to go in during the draft, so he’s called a “no no boy,” which haunts him and his family. It’s a steady novel that’s more thoughtful than fast, and I used to teach it in a lit class.

Sounds interesting! Hotel on the Corner is also set in Seattle, which I enjoyed – I had never thought of Seattle’s history much before reading the book.

Thanks for the suggestion!

Great connections and review Naomi!! I read The Translation of Love as well and really enjoyed it! I just never put those thoughts together, quite so well like you have here. 🙂 I loved all the different voices in the book. I loved the connections you made to other novels too! I read The Buddha in the Attic and absolutely loved it. It’s very different, and such a tiny book is so incredibly powerful – it’s told in the collective.

I think you’re the reason I decided to read this book, Penny! I remembered that you liked it. There weren’t a whole lot of other reviews out at the time.

Thanks for your kind words! 🙂

Another great historical fiction recommendation! Thanks, Naomi.

You have uncovered a gap in my reading history. There are so, so many! So I can’t recommend any books about Japanese/Canadian Americans during the war. Naturally, I must look for books that I can read to fill this gap and this one will certainly go on that list.

There are just too many interesting things to read about, aren’t there? But I’m glad I was able to bring this one to your attention. 🙂

I’m due for a re-read of Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet!

It’s definitely one that’s worth re-reading!

That’s an interesting combination. I have been wondering if I wanted to read Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet. I’ve been worried that it will be too much of a feel-good novel. They seem to be really popular now, but I find them rather saccharine.

I don’t think I’d call Hotel on the Corner a feel-good novel. One part in particular I found really sad. It’s one of those ‘if only things had been different’ books. I think you should try it – I really liked it!

Well, that makes it sound more interesting. I will probably try it sometime.

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet has been on my bookshelves for a while now, so I’m excited to hear you mention having enjoyed it! I’m hoping to get to it soon 🙂

I thought I was the only one left who hadn’t read it, but I guess not! I hope you love it!

This sounds like a great book, with a powerful story. Thanks for review!

I thought it was great! I hope you get a chance to check it out!

Thanks for nudging this one up my TBR. It really sounds like a great collection of characters. And I love the quote about hunger and longing1

Another on the experiences of imprisoned families in the U.S. is Vivienne Schiffer’s Camp Nine, a first novel which focusses on the experiences in the camp. Such an important topic!

This is the first I’ve heard of Camp Nine. You’re always good for new recommendations!